Our Local Heritage

The articles reproduced here have all been published in the Villages Mag in a regular feature.

2023

2022

A Landowning Dynasty - the Hodges Family

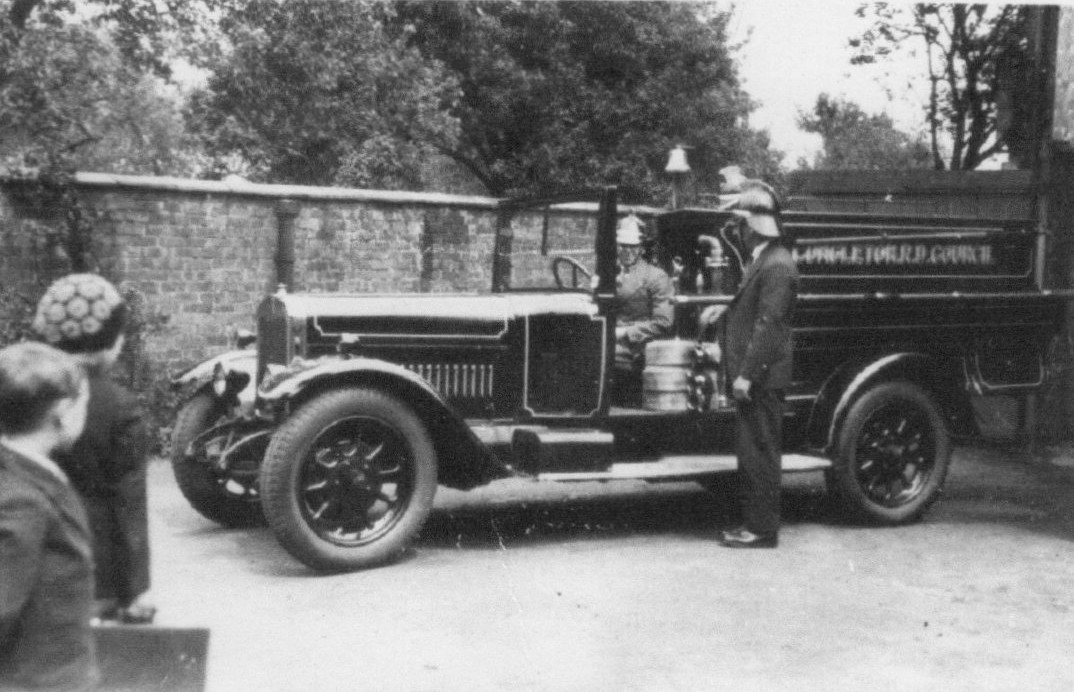

The Fire Service in Holmes Chapel

2021

Christmas Past in Holmes Chapel

2020

The College of Agriculture & Horticulture

Thomas Royle Kay - WW1 Soldier

Spy, Red Lion & Piece of Glass

2019

The Jackson Family & Wallpaper Works

The Holmes Chapel Rail Crash of 1941

2018

Early Years of St Luke's Church

Armistice Day in Holmes Chapel

2017

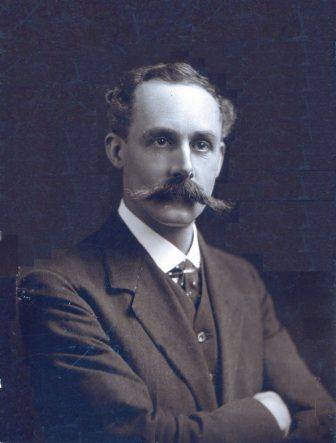

David Elks

This is the first of a regular feature which will delve into the characters and buildings of our village and surrounding area. Who knows Holmes Chapel was the birth place of a world famous golfer, experienced its own ‘Great Fire’ in 1753 and saw significant change with the coming of the railways? Future articles will provide the answers.As this first article is being published in mid November, just after Remembrance Sunday, we have recalled one of the men lost during the Great War. David Elks was a wallpaper printer at the Holmes Chapel Wallpaper Works which was on the same site as Fads on Macclesfield Road.

He joined the forces in 1917 and after that time was involved in the battles of France and Flanders. We know in October 1918 he was in hospital suffering from gas poisoning. Sadly, he returned to service immediately afterwards and was killed in action on 1 November 1918.

He moved to Holmes Chapel in 1911 to join the work force at the new wall paper works having been in the same trade in Pendleton near Manchester. He left behind a wife, Edith, and two young children who were living at Church View.

David Elks was only one of 225 men who were serving in the forces during the First World War with connections to Holmes Chapel. Of those, a total of 31 died during the conflict.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" December 2017

Click here to return to top of page.

The Construction of Holmes Chapel Viaduct

The railway viaduct, an important feature in our landscape, was built as part of the Manchester and Crewe Junction Railway between 1840 and 1842. The line was opened as part of the Manchester to Birmingham Railway Company as far as Sandbach on 13th May 1842. The engineer in charge of construction of the line was George Watson Buck a canal and railway engineer, and a stone with his name and the date 1841 was placed at Goostrey station where it can now be seen mounted on a wall on the Manchester platform.

Holmes Chapel’s population easily doubled during the construction of the viaduct. In the census in 1831, the population was 406. During construction in 1841, it rose to 1008, and afterwards in 1851 it fell back to 555. Over 500 people were involved in the building of the viaduct – masons, bricklayers, carpenters and a vast number of “navvies” whose dress and outlook made them a distinct social class. There was no accommodation for such numbers in the village, and most lived in a camp adjacent to the viaduct. Because of demands on local bakers, sometimes navvies had to walk four miles to Middlewich for a loaf of bread.

The viaduct is the longest on the line at 1794 feet with 23 arches each of 63 feet span, a considerable feat of engineering for over 150 years ago. Stockport viaduct is higher, but is also slightly shorter.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" February 2018

Click here to return to top of page.

The origins & early years of St Luke's Church Holmes Chapel

|

|

The early history of St Luke’s Church in Holmes

Chapel is not clear, but there is a possibility that the site where the

church now stands was a place of pagan worship before a church was

built. The earliest indication of there being a church is 1265 when the

abbot of Dieulacres Abbey near Leek gave permission to the abbot of

Chester for services to be held in the “Chappell at Church Hulme”. We

don’t know what that church looked like but as Holmes Chapel was even

then at a busy North-South and East-West cross roads perhaps we should

not be surprised that funding was provided for a new church in the

1430s. We believe this was donated by the Needham family who came from

Derbyshire and settled in Cranage. The church they built would have

been black and white timber framed building, a bit smaller than now but

with the tower and wonderful vaulted roof as we see to this day. The

church used to have tombs and stained glass in memory of the Needham

family but they have all vanished.

During the Civil War there was a skirmish between Royalist and

Parliamentary soldiers on 26th December 1643 and shots were fired from

approximately where Barclays Bank is now. Two men were killed. You can

see the musket ball marks on the tower to this day, which are strongly

believed to be as a result of the skirmish.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" March 2018

Click here to return to

top of page.

Rudheath - a Wild & Lawless Sanctury

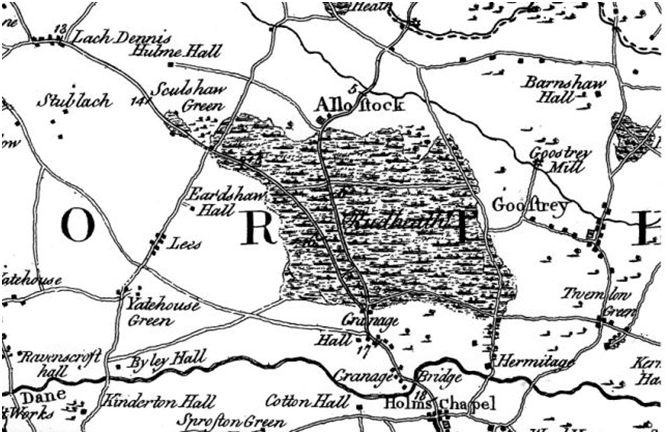

The Rudheath area of Allostock and Cranage including Woodlands Park, Shakerley Woods, BoundaryBarn and Rudheath Lodge was once a wild and lawless sanctuary for criminals.

In early mediaeval times Rudheath was one of three Cheshire sanctuaries provided for criminals under the powers granted to the Earls of Chester. Rudheath Sanctuary used to stretch from the edge of Northwich through Allostock and Cranage to Goostrey. In this extensive wood containing swamps and thickets fugitives were allowed to live provided they paid a fine to the Earl of Chester and fought for him when called on. These were difficult times. 1349 saw the onset of the Black Death and in 1353 there was an uprising against the Black Prince, Earl of Chester and his officials. Rudheath was notorious for outlawry, murders and violence. Eventually “in consequence of grievous clamour and complaints ---of many robberies and murders” an act of parliament was passed to prevent “outlawry” and impose “forfeiture of goods”. Even after this, areas of Allostock and Cranage bore a bad name as wild and lawless places.

In May 1644, Prince Rupert with 10,000 men camped on the great remaining spaces of Rudheath, Knutsford Heath and Bowdon Downs.

By 1777 Burdett’s map shows the Rudheath woodland in Allostock and Cranage had been much reduced by enclosures.

Alan Garner’s novel “Red Shift” is partly placed in the once lawless heathland waste in Allostock where Woodlands Park is today.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" April 2018

Click here to return to top of page.Henry Cotton - Our Local Golfing Ledgend

Many people, even those not players of golf, will have heard of Henry Cotton. Who knew that this legendary golfer was born in Holmes Chapel?

Born on 26 January 1907 at ‘The Croft’, a large house on Macclesfield Road Holmes Chapel, now demolished. Henry’s father, George Cotton, owned the Victoria Works next door which produced Steam Hot Water Boilers. This is now the site of the wallpaper business. George, a widower, remarried in 1904 to Alice Le Poidevin and they had three children, including Henry, all born at The Croft. In December 1910, Henry then aged 4, the factory and house were sold and the Cotton family settled in South East London. Henry and his older brother later attended boarding school in Dulwich. Although a good cricketer Henry loved golf and turned professional in 1924, aged only 17. He was soon a golfing star winning the 1934, 1937 and 1948 Open Championships, the U.S. Open in 1956 and numerous other tournaments.

During World War II he served with the RAF and raised money for the Red Cross by playing exhibition matches. This earned him an MBE.

He retired from competitive golf in the early 1950s and became a successful architect of golf courses, wrote 10 books and established the Golf Foundation helping young boys and girls get started in golf. Henry Cotton loved the high life, champagne, caviar and bespoke tailored clothes and bought an estate complete with butler and full staff. He traveled everywhere in a Rolls-Royce He died in December 1989 in London.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" May 2018

Click here to return to top of page.Heavy Industry at Cranage?

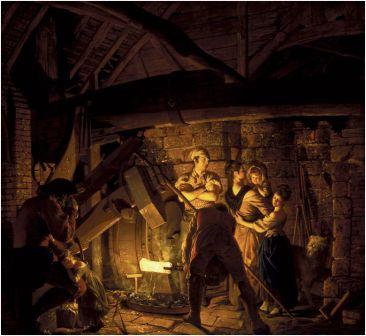

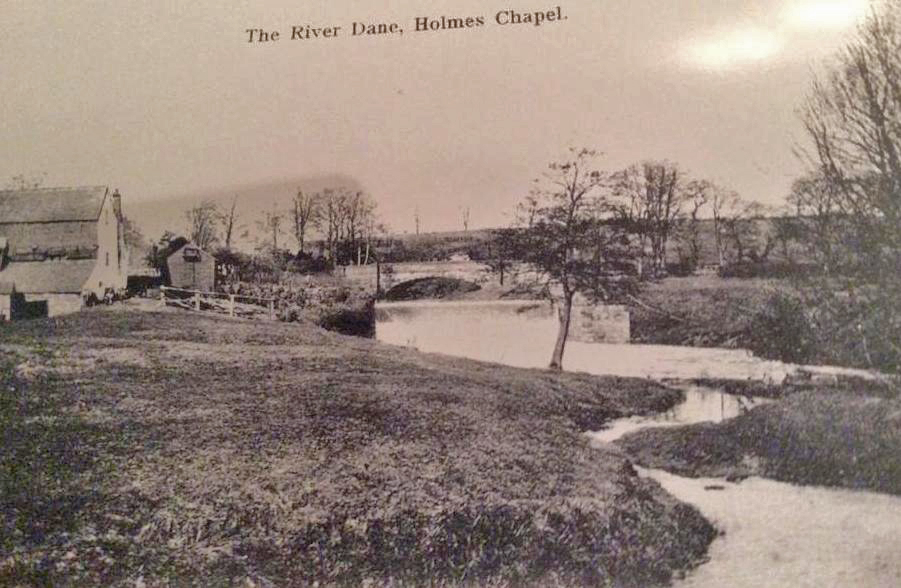

Cranage Forge was situated alongside the River Dane on the site of Massey’s Mill which was an ideal site for heavy industry in the 17th Century. Its location provided water power for the finery, the chafery and the slitting mill and access to woodland for charcoal. The Forge was well sited on the main north-south route between Lancashire and the Midlands for the movement of the finished products. The earliest record of the Forge is the 1660s with information concerning the purchase of wood for charcoal, which at that time was the main heating fuel.

The main activity was the refining of pig-iron into wrought iron. The pig-iron came mainly from the furnaces at Church Lawton and Vale Royal. The first process was carried out in the finery, where the pig-iron was repeatedly heated in the hearth and hammered until the remaining carbon was beaten out. At the chafery hearth the hammer man would reheat the iron again to be drawn out into bars. Some of the bars would be worked through the slitting mill into rods for the nail making trade. Estimates of the amount of wrought iron produced at the Forge may have reached over 150 tons per year at peak times. By the 1750s the use of coke, rather than charcoal, in the smelting of iron and other factors brought to an end the iron industry at Cranage. The site continued as a mill utilising the water power for silk production and flour milling into the 19th century.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" June 2018

Click here to return to top of page.The Great Fire of Holmes Chapel 1753

A report in the Manchester Mercury dated 17th July 1753 stated that on the “previous Tuesday (10th July 1753) a fire broke out in the house of a button-maker in Holmes Chapel. There was a high wind and in a few hours 15 out of the 19 houses in the town were reduced to ashes”.

The buildings which escaped the fire were the church, the Red Lion and the cottages behind the church with low roofs. The fire came very close to the Church. Lime trees which circled it, planted in 1743, were scorched but survived. They were removed in 1960 because they had become decrepit and dangerous.

At the time of the fire most of the inhabitants were at a monthly meeting in Northwich. As a result there appears to have been no loss of life. A consequence of the fire is that the oldest buildings in the village, except those mentioned, are late 18th/19th century.

There is no known record of how the fire was put out or what equipment was available at the time in Holmes Chapel. However fire engines were in existence in the country at the time.

The earliest references to an “engine” in Holmes Chapel is found 1866. However in 1892 some willows thought to have been behind the present Sainsbury’s and Costa caught fire “and in a few minutes about 50 dozen hampers and 50 tons of dry willows, together with the shed that contained them, were in one monstrous blaze”. It is stated that water was brought from pumps in buckets to bring the fire under control as it was no use getting the fire engine out because there was insufficient water to feed it.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" August 2018

Click here to return to top of page.Holmes Chapel on Armistice Day 1918

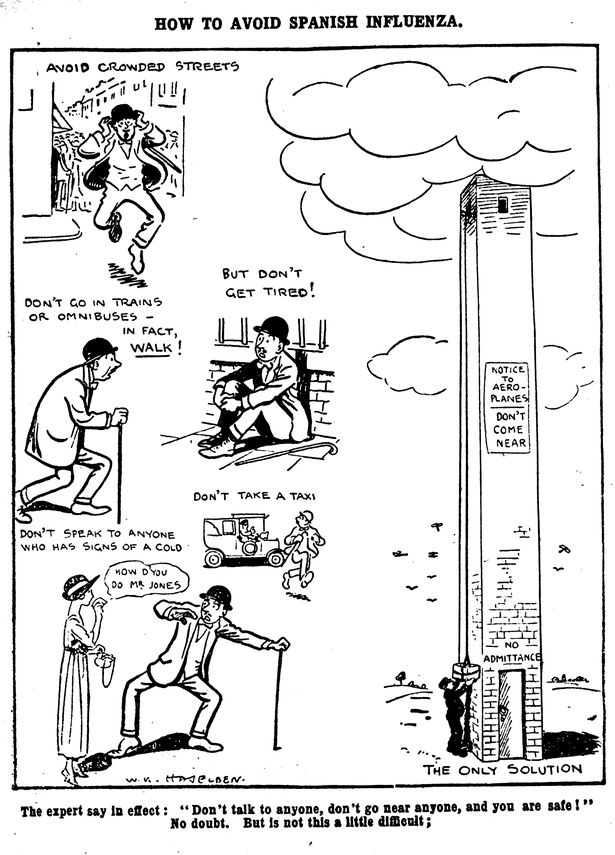

In November 1918, Holmes Chapel village was at a low ebb. Not only had 28 members of the community died at the Front over the past four years (out of a population of 926 residents in 1911), but also Spanish flu had broken out a few weeks earlier. Both Cranage School & Macclesfield Road County School were closed because of the epidemic on Wednesday 16th October, and did not reopen until 18th November. Saltersford College was also seriously affected. Flu also impacted the Paper Works on Tuesday 15th October when 13 were compelled to cease work. A dance was cancelled on 25th October due to the epidemic, and four deaths were reported in the newspapers as being due to influenza between 27th October and 6th November.

On Monday 11th November, when news of the Armistice reached Holmes Chapel, the local mills ceased work, and employees were given a three day holiday. However, there were no holidays at the schools because they were already closed. The village centre was quickly dressed with an abundant display of flags and bunting, and peals were rung on the church bells until nearly midnight.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" September/October 2018

Click here to return to top of page.The Bells of St Luke’s Church, Holmes Chapel

One of the pleasures of living in Holmes Chapel is hearing the bells of St Luke’s as they call worshippers to church and mark special occasions, both happy and sad. The bells have a long and interesting history.

There are seven in total, six of them dating back to the early years of the eighteenth century, though one was recast in 1858 and the original inscription replaced by the founder’s name: G. Mears of London. The seventh bell was cast by the same firm and bears the same date and inscription.

The smallest bell is dated 1706 and is known traditionally as

the Dagtail or Draggletail Bell. It would be rung hourly between 6am

and 6pm for the benefit of the workers in the fields, most of whom

would not possess a watch. Its name derives from its other use of

calling last minute stragglers to church services. The other five, and

maybe the Draggletail too, were given to the church by Daniel Cotton

(1660 – 1723), one of the family of ironmasters who owned Cranage Forge

and other ironworks in the area. All the bells were inscribed with

short phrases such as:

“I’le sally forth Queen Anns Great Worth. The gift of Daniel Cotton,

Ironmaster, 1709.”

|

The religious and political disagreements which had led to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had not diminished by the reign of Queen Anne (1702 – 1714). The French King Louis XIV sought to dominate Europe and restore the Catholic Stuarts to the English throne. Thus, with this quotation, Daniel Cotton was able to demonstrate his loyalty to the Crown and keep the villagers of Holmes Chapel informed of the great events of the time.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" November 2018

Click here to return to top of page.

A Bit of Scandal - Agnes Needham

Agnes was a Needham, the family believed to have financed the re-building of St Luke’s Holmes Chapel in the 1400s. They had two estates, one at Cranage and the other at Shavington in Shropshire. Agnes was born at Shavington in 1547 but would have visited Cranage Hall.

She became the second wife of Sir Richard Bulkeley, Sheriff of Anglesey and Constable of Beaumaris Castle. They lived at Baron Hill in Anglesey. The house was rebuilt by Sir Richard’s son by a previous marriage, Richard (See photo below).

|

|

Agnes gave Sir Richard 2 sons,Launcelot (later Archbishop of Dublin), and Arthur. She and stepson, Richard did not get on. Once Agnes’s husband, Sir Richard had died after an illness, stepson Richard demanded his younger brother John marry a local heiress. However Agnes had arranged for Arthur to marry her. Next thing, Agnes is accused of murdering her husband. Poison is found in a chest in her room under some slippers. She is also accused of adultery with William Kendrick “a young gallant” who “did use to walk under her window in the night time, play upon an instrument and make love to her” when Sir Richard was away.

After a court case lasting 3 years Agnes was acquitted of murder but found guilty of adultery.

Having married again- to Lawrence Cranage of Keele, she lived the rest of her life and was buried (Jan 1622/3) in Holmes Chapel.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" February 2019

Click here to return to top of page.Dr Lionel James Picton - The Village Doctor

For 45 years the inhabitants of Holmes Chapel and district were fortunate to have him as their doctor.

Born in 1874 at Bebington, Cheshire, he qualified at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital London in 1900 and came to Holmes Chapel in 1903. In 1904 he married Mary Emma Binney, a nursing sister. They later had six children. The Doctors surgery was at his home, Sadlers Close, off Knutsford Road. Mrs Picton worked with him, making the medicines.

Dr. Picton was a familiar figure, wearing a cloak and a wide brimmed hat and riding his horse, his mode of transport until he got his first car - a de Dion Bouton. Highly respected, there are many reports, ‘Dr. Picton attends’, at whatever time of day or night.

He had strong views on nutrition and wrote a book ‘Thoughts on Feeding’ about the benefits of good nutrition, soils, grains, and he even developed a breed of cattle, which was eventually lost to Foot and Mouth disease. Woe-betide a household with white bread on the table when he visited, he just threw it away.

During the First World War Dr Picton spent time at a field hospital in Calais and was the Medical Officer for Somerford Hospital, which cared for wounded soldiers.

Doctor Picton was awarded the OBE in 1920. He died on November 19th 1948 at the age of 74. Some people today still remember him, as do others his son, Dr.Arthur Picton (Dr. Arthur), who followed him in the practice. Picton Square is named after Dr. Lionel.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" March 2019

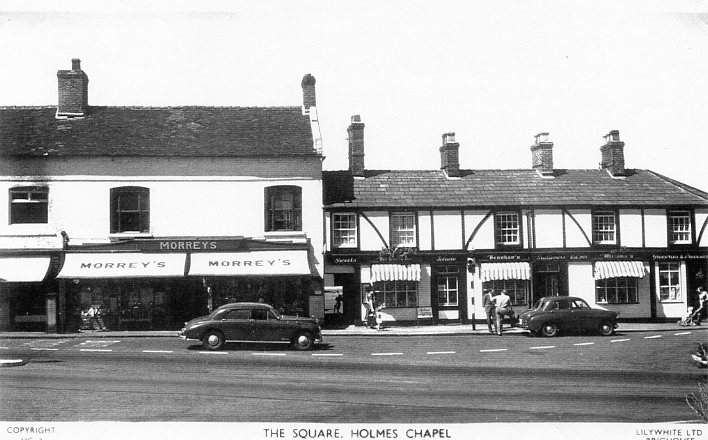

Click here to return to top of page.Morreys of Holmes Chapel

Now relocated to the trading estate on Manor Lane, the original site of this long-established business was in the village centre: it is now occupied by Costa and Sainsburys.

By 1850 Thomas Morrey was working as a cooper. He was followed by his sons: William carried on the barrel making and Arthur started a drapery, reputedly in the basement. What had been Forshaw’s gas showroom was absorbed into Morreys, becoming the paint shop. Apart from paint, here you could buy paraffin for the domestic heater. It was pumped from a can kept at the back of the shop. At the north end, what had been Plant’s saddlery became the gentleman’s outfitter department of Morreys, run by Len Tallon. Len neatly wrapped every purchase into a brown paper parcel tied with string. In the era of David Morrey the upstairs gradually became the bike showroom and the top storey was used as a store. The stock of electric lamps, being light weight, was kept at the furthest extremity deep into the attic, through a series of small rooms. There was an office at the back of the shop where Mrs Thomas calculated the wages on her hand cranked calculator. Behind this was a bike repair shop. In the 1950s Morreys had a branch in Middlewich, run at one time by Albert Rathbone. There it was possible to buy a small amount of paint tipped out of a full can!

Morreys is the oldest surviving family business in the village and from 1850 until the move to Manor Lane was always partly staffed by members of the family.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" April 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope

The story of the Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope began in 1945 when, after wartime service researching radar, Bernard Lovell came back to the University of Manchester to observe cosmic rays. A quiet observing site was needed and the University’s botanical station at a little-known place called Jodrell Bank, 20 miles south of Manchester, proved to be the ideal location.

Bernard Lovell worked with engineer Charles Husband, to build the 76-metre telescope. Initially named the MK 1 Radio Telescope, it was renamed the Lovell Telescope on its 30th anniversary in l987. It became an icon of British science and engineering and a landmark in the Cheshire countryside.

The telescope was the world’s largest when completed in 1957 and within days tracked the rocket that carried Sputnik 1 into orbit, marking the dawn of the space age. It is still the third largest steerable telescope in the world and many upgrades mean it is now more capable than ever, observing phenomena undreamt of when it was first conceived.

In 2017 the Lovell Telescope celebrated its 60th anniversary and has been selected as the next UK candidate to go forward for nomination to UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Other notable sites across the world include the Grand Canyon in the United States and Machu Picchu in Peru. Many of the structures at Jodrell Bank are protected by Historic England in recognition of their importance in the history of astrophysics. Still owned by the University of Manchester, the site includes the Jodrell Bank Observatory and a thriving Discovery Centre.

Over the years it has provided employment for many local families, both in the research department and the visitor centre, who all enjoyed the pleasant surroundings of the Cheshire countryside.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" May 2019

Subsequently, in July 2019, Jodrell Bank was made a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Click here to return to top of page.

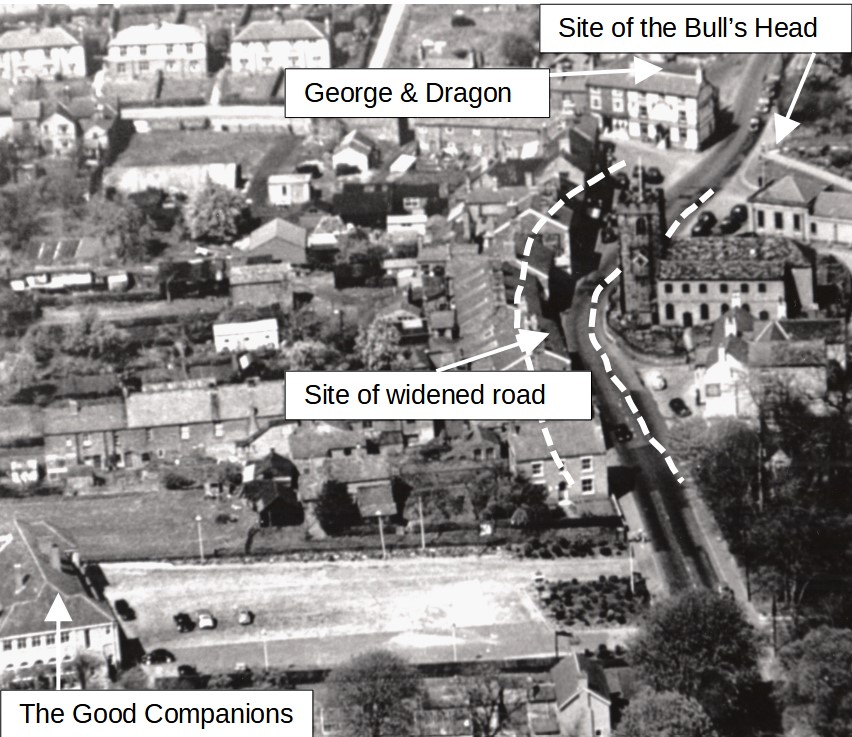

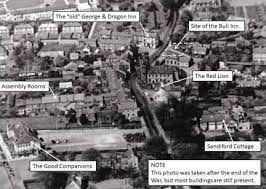

The Good Companions Cheshire's New Hotel Deluxe

The following is based on an article in the Crewe Chronicle on 25th March 1939. “The Good Companions” was opened by the famous actress Jessie Matthews who starred in the 1933 film "The Good Companions", based on the novel by J.B.Priestley:

“On Tuesday 14th March 1939, the Bull’s Head, owned by Wilson’s Brewery, closed its doors as a licensed house, and transferred the licence to the new hotel which opened on the following day. It is an imposing building, set back from one of the busiest main roads in the country, luxuriously furnishedwith nothing omitted for the comfort and enjoyment of patrons."

"On the ground floor there are a small bar; splendidly furnished smoke rooms and lounges; an attractive dining room with high-backed chairs; and a large room for meetings. The several bedrooms have hot and cold water laid on, and also upstairs is a spacious dance room. There is an orchestra whose playing is relayed to the various rooms by speakers which are cleverly hidden in ventilators which are covered with mural decorations depicting scenes from the book. There are similar scenes on the frosted glass doors and beneath the banister rail of the main staircase. At the rear of the building, facing tennis courts and a bowling green with pavilion, is a loggia with creepers and a tea garden where there will be open-air dancing in the summer. Hundreds of shrubs have been planted around the grounds.”

The hotel was a popular “road house” but lost business once the M6 by-passed the A50. It closed in 1992 and was later demolished.

Lovell Court now occupies the site.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" June 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

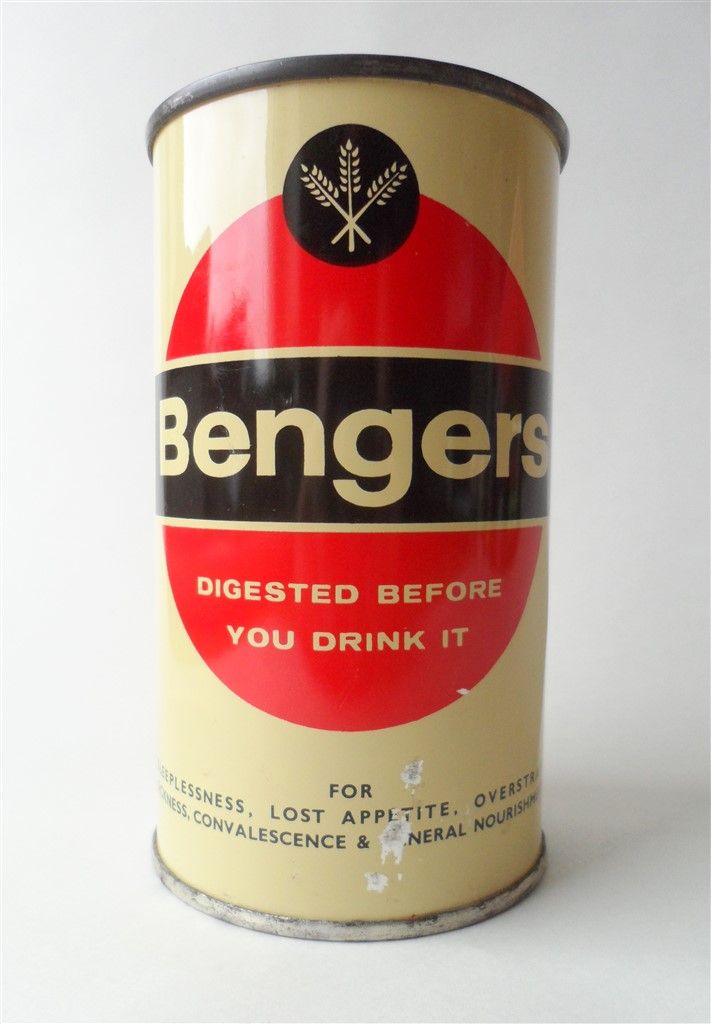

The Benger's Factory

Some people are probably unaware of the nutritious food supplement known as Benger’s, which at one time was regarded as essential in the care of young children, expectant mothers and invalids, and of the fact that it was manufactured in Holmes Chapel in a state of the art building on London Road near the railway bridge. At its peak Benger’s was the major employer in Holmes Chapel and played an important role in the day to day life of the village. Its sports and social club was well attended and frequently used as a venue for local events.

Benger’s Foods, originally Mottershead and Company of Manchester, was acquired in 1870 by Frederick Baden Benger and Standen Paine, both pharmacists. It was renamed as Benger’s Food Ltd in 1903 and in 1938 was relocated to purpose built premises in Holmes Chapel. The Head Office, in an “ imposing but restrained” Art Deco style, and the factory were designed by the architectural practice of J H Andrews and Butterworth, Manchester, which specialised in the design of industrial buildings.

The Benger House building

was a fine example of the new "daylight factory" introduced into this

country during the 1920s. The aim was to make the workplace more

efficient and more pleasant for the labour force. Among the impressive

features was a domed lantern in pink and blue glass which lit the

staircase in the entrance hall and the glazed wall and floor tiles of

the manufacturing areas. In 1947 there were 350 employees and Bengers

Food was bought out by Fisons Ltd. Their pharmaceutical division based

in Holmes Chapel with its portfolio of asthma and anti-allergy drugs

was by far the most profitable of the company.

The Benger House building

was a fine example of the new "daylight factory" introduced into this

country during the 1920s. The aim was to make the workplace more

efficient and more pleasant for the labour force. Among the impressive

features was a domed lantern in pink and blue glass which lit the

staircase in the entrance hall and the glazed wall and floor tiles of

the manufacturing areas. In 1947 there were 350 employees and Bengers

Food was bought out by Fisons Ltd. Their pharmaceutical division based

in Holmes Chapel with its portfolio of asthma and anti-allergy drugs

was by far the most profitable of the company.  The Fisons group was dissolved in 1996 and the site and buildings were

acquired first by Rhone-Poulenc and then by Sanofi Aventis, who built a

brand new factory. The former Benger House was not included in the

redevelopment plan and it sat empty with little to show of its former

usage. It was a sad sight to see the once lovely building fall victim

to the ravages of time and the encroachment of nature. An application

to assess the building for listed status was received by English

Heritage in 2011 but was turned down because,

The Fisons group was dissolved in 1996 and the site and buildings were

acquired first by Rhone-Poulenc and then by Sanofi Aventis, who built a

brand new factory. The former Benger House was not included in the

redevelopment plan and it sat empty with little to show of its former

usage. It was a sad sight to see the once lovely building fall victim

to the ravages of time and the encroachment of nature. An application

to assess the building for listed status was received by English

Heritage in 2011 but was turned down because,

"While the frontage of Benger House has characteristic late Art Deco

features it does not exhibit sufficient interest or intactness

associated with the Art Deco style though it is clearly of strong local

interest."

It is thought that the location of the building in the then small

Cheshire village of Holmes Chapel may have modified any greater

flamboyance in the design.

The building was finally demolished in August 2015 and the site is now for sale for redevelopment.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" July 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

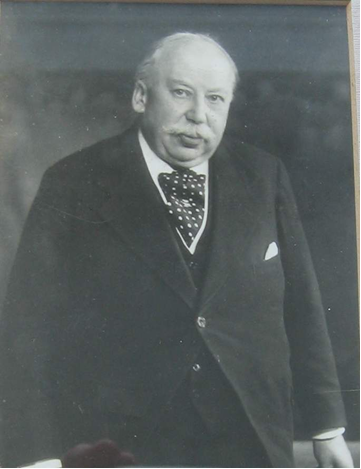

The Jackson Family and the Wallpaper Works

The wallpaper works on

Macclesfield Road (now FADs) has been operating in Holmes Chapel since

1911 when George Fenton Jackson took over the site with his colleague

James Walker. Both had been employed in the wallpaper business in North

Manchester and appear to have decided to establish their own business

in Holmes Chapel. George’s father, also called George, was a skilled

engraver so it was not surprising his son was described as a gifted and

talented wallpaper designer. Where his ambition to open his own

business came from is unknown.

The wallpaper works on

Macclesfield Road (now FADs) has been operating in Holmes Chapel since

1911 when George Fenton Jackson took over the site with his colleague

James Walker. Both had been employed in the wallpaper business in North

Manchester and appear to have decided to establish their own business

in Holmes Chapel. George’s father, also called George, was a skilled

engraver so it was not surprising his son was described as a gifted and

talented wallpaper designer. Where his ambition to open his own

business came from is unknown.

The factory site on Macclesfield Road had originally been a horticultural builders works where iron framed greenhouses were produced. Henry Cotton, who later became the world famous golfer, lived in a house on the site when he was a child.

The site was purchased in 1911 for the sum of £2600 by George Jackson and James Walker and they set up the Holmes Chapel Wallpaper Company. James Walker seems to have moved on and the business in Holmes Chapel was run by the Jackson family for three generations.

Apart from providing employment they had a major impact on the appearance and social activities of the village. It was Alfred Jackson, George’s son, who built the houses along Victoria Avenue and London Road and provided the Victoria Club as a social venue for staff and the community. Alfred also built several other houses in Holmes Chapel and as his daughter in law Dorothy Jackson said, ‘He liked to live life to the full and was always on the lookout for a trip or a project’. Alfred was very much involved in the community: he was a JP and Chair of Congleton Borough Council in the 1930s. George Fenton was also a serial house builder: two houses on Chester Road and ‘Twemlow Edge’ overlooking the River Dane from the Twemlow side were built by him.

In the next generation Sidney Jackson, son of Alfred, was a keen sportsman. He volunteered for the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the Second World War, was wounded at Dunkirk, took part in the Arctic convoys and learnt to play tennis in Alexandria. He settled into a house in Station Road and lived there until he died in 2002. His wife Dorothy was very involved in the community as a JP and Chairman of the Parish Council on several occasions. Some of the family, although not involved in the wallpaper works, still live in the village and continue to play a part in community activities.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" September 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

The 1941 Holmes Chapel Rail Crash

At about 1:20 am on Sunday 14th September 1941, a serious rail crash occurred at Holmes Chapel Station when nine people were killed, six in the accident and three more died later. Forty five passengers were injured, with 21 being detained in hospital. The accident involved a Crewe – Leeds Express, a mail train, which was almost stationary in the station, and a Crewe – Manchester train, which ran into the rear destroying the last two passenger coaches of the Leeds Express.

As the trapped passengers

struggled in the darkness, airmen and soldiers from the undamaged

coaches on both trains went to the rescue. Prompt measures were taken

by the resident Station Master and his staff who were awakened by the

crash, and by the Sergeant in charge of the Police Station, who

summoned medical assistance and ambulances, and initially attended to

the injured. Doctor Picton arrived at 1:40 am, and the first ambulance

arrived at about 2 am.

As the trapped passengers

struggled in the darkness, airmen and soldiers from the undamaged

coaches on both trains went to the rescue. Prompt measures were taken

by the resident Station Master and his staff who were awakened by the

crash, and by the Sergeant in charge of the Police Station, who

summoned medical assistance and ambulances, and initially attended to

the injured. Doctor Picton arrived at 1:40 am, and the first ambulance

arrived at about 2 am.

Villagers awoken by the

sound of the crash ran to the station with blankets and supplies of hot

water. Home Guards and local ARP workers joined the rescue gangs. The

Swan Inn was converted into a temporary dressing station where the

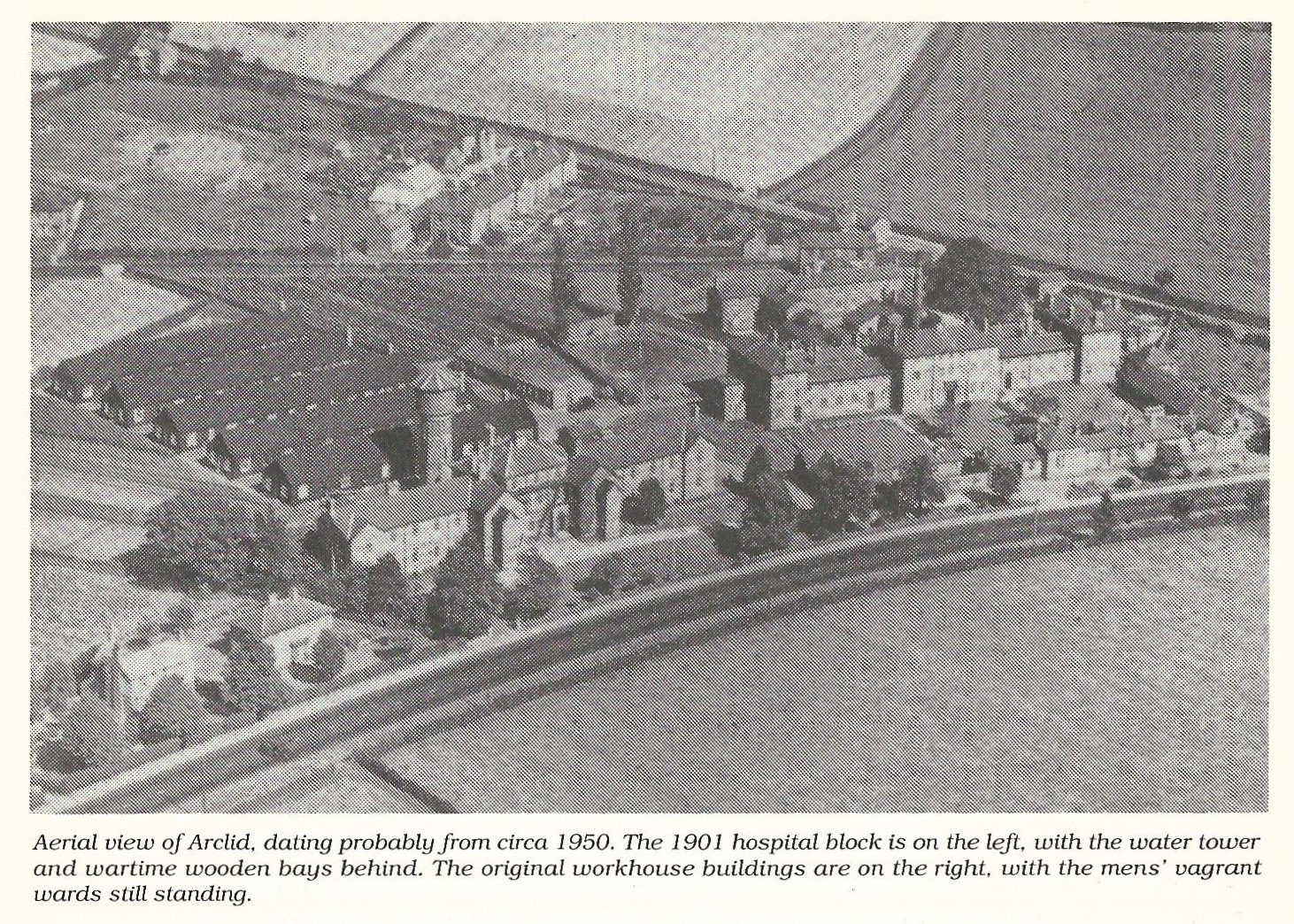

injured received attention before being taken to Arclid Hospital in

ambulances summoned from all parts of Cheshire. All the seriously

injured had been removed to the hospital by 3:15 am.

Villagers awoken by the

sound of the crash ran to the station with blankets and supplies of hot

water. Home Guards and local ARP workers joined the rescue gangs. The

Swan Inn was converted into a temporary dressing station where the

injured received attention before being taken to Arclid Hospital in

ambulances summoned from all parts of Cheshire. All the seriously

injured had been removed to the hospital by 3:15 am.

The dead were recorded as:

* Pilot Officer William Evans (25), of Newport, Monmouthshire

* Private Claude Lowder (22) of Spring Grove, Fenay Bridge,

Huddersfield, Yorkshire

* Sergeant John McCrae (31), RAF, of Park Avenue, Skipton, Yorkshire

* Private John Lennox (24), OCTU, of Jersey Avenue, Stanmore, Middlesex

* First-class Aircraftman Jeffrey Williams (23), of Hull

* George Christie Lowe (39) of Eden Street, Oswestry

* Reginald Gregory (35), Railway Guard, of Llanfair, Pear Tree Lane,

Wednesfield

* Stoker J Foster (26) RN, of Grimsby

* Eileen Ann Pritchard (13 months old) of Derby Terrace, Wrexham who

was travelling with her mother, who was seriously injured.

After an Inquest held at the Victoria Club, and a formal Inquiry at the Crewe Arms in Crewe, it was deemed that the crash was due to a number of factors, including old signalling technology that had been due to be replaced and the demands placed on signalmen working single handed on 12 hour night shifts 6 days per week. Of course, another important factor which was not mentioned at the Inquiry was that the crash occurred during the Second World War, in the middle of the night, when a complete blackout was in operation.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" October 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

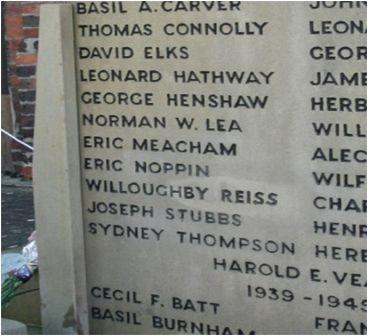

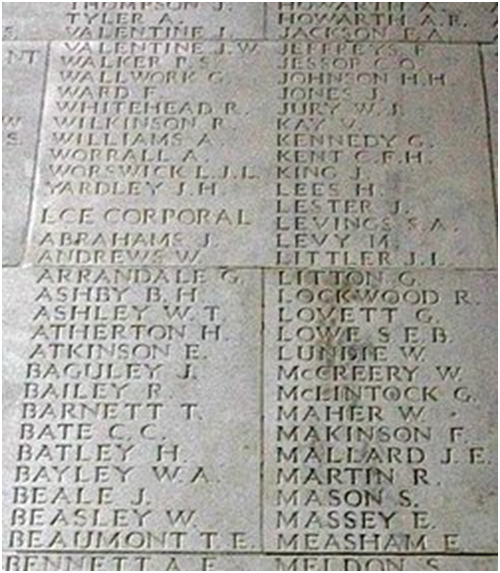

A Grave Spelling Mistake

Well

more a WW1 Memorial spelling mistake – because we now believe Eric

Meacham (with a ‘C’), recorded on the Holmes Chapel Memorial was in

fact Eric Measham (with an ‘S’). It is quite surprising that this

error, visible for so long, has gone unnoticed but a number of factors

contributed. Firstly the memorial at St Luke’s church was not created

until after WW2 so it appears the name was copied from the Roll of

Honour in the church where the original error seems to have been made.

Well

more a WW1 Memorial spelling mistake – because we now believe Eric

Meacham (with a ‘C’), recorded on the Holmes Chapel Memorial was in

fact Eric Measham (with an ‘S’). It is quite surprising that this

error, visible for so long, has gone unnoticed but a number of factors

contributed. Firstly the memorial at St Luke’s church was not created

until after WW2 so it appears the name was copied from the Roll of

Honour in the church where the original error seems to have been made.

We know an Eric Measham existed along with brothers Harry, Fred and George from census records. Those three brothers are also mentioned on the Roll of Honour with the same spelling mistake! From his military records we know he lived at the Cranage Club, now Cranage Village Hall, for a while where he was probably working for the Carver family at Cranage Hall.

The Parish magazine of March 1917 states ‘E. Meesham is officially reported missing’ and in July 1917, ‘Eric Measham missing since last July has been officially reported dead.’ There is clearly confusion over the spelling of his name at the time and it appears that the wrong option was selected when the memorial was constructed.

It is probable that the family moved away shortly after the end of WW1 and so, sadly, were not around to point out the error.

|

|

Eric Measham has no war grave but he is recorded (correctly spelt) on the Thiepval Memorial in France.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" November 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

Cranage Hall

The manor of Cranage was mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086 and it is possible that a hall was built there not long afterwards. By the seventeenth century a “brick mansion house” occupied the site, though this was demolished when the present building was erected in 1829. For centuries the Hall was the centre of a large agricultural estate and the home of a series of wealthy families, most notably the Needhams, who acquired the property by marriage to the heiress Alice Cranach. In 1625 Sir Robert Needham was created Viscount Kilmorey, though by then the main branch of the family had moved to Shropshire and other relatives occupied the Hall. It was sold in 1660 to William Swettenham and sold again in 1679 to the Reverend William Harrison, who was the son of a Tatton farmer. Most of the land remained in the ownership of the Needhams until 1760, when the manor was sold to Thomas Bayley Hall of the Hermitage. Several generations of Harrisons lived at Cranage Hall until it was sold to the Reverend John Armitstead, vicar of Goostrey, in 1814. In 1828 his son Lawrence bought the neighbouring Hermitage Estate and commissioned Lewis Wyatt to build the fine new house at Cranage where he lived until his death in 1874. A cousin, the Reverend John Richard Armitstead, Vicar of Sandbach, inherited and occupied the Hall from 1877 to 1918. His son, the Reverend John Hornby Armitstead, Vicar of Holmes Chapel from 1899 to 1918, was the last Armitstead to live there. In 1900 the Hall was leased to William Oswald Carver, owner of a cotton mill in Marple, who purchased the estate in 1920. By 1927, having lost two of his sons in the First World War, he decided to downsize, moved to Hartford Hall, and put Cranage up for auction. Its days as a family home were over.

It was not until 1929 that the Hall and grounds were acquired by the local health board for use as a mental hospital. The Hall housed the offices and the Cranage Colony, a small village in its own right, was built in the grounds. This included residential villas, a social hall, swimming pool, shop, cafe and maintenance buildings. The Colony employed many local people and its closure in 1995 shocked the community. The Hall fared particularly badly in the three years it lay empty, with thieves taking all the oak panelling, doors, floorboards, fireplaces and even the main staircase! Thankfully, it was purchased by a hotel group and comprehensively renovated, retaining its status as a Grade 2 listed building. Today it is the DeVere Cranage Estate Hotel and conference centre.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" December 2019

Click here to return to top of page.

Holmes Chapel Before the M6

The Staffordshire to Preston section of the M6 through Cheshire opened in November 1963. Before then London Rd, the A50, was the main north route to Scotland west of the Pennines. This meant that all the trunk road traffic had to pass through Holmes Chapel and squeeze past the church. It was great entertainment for the children, on hearing a heavy load coming through the village, to dash towards the Square to watch the load being inched around the church. The building now occupied by Latham Estates has scars in the brickwork as evidence of these struggles. In those years, if the firemen were needed for an emergency call, the siren would sound out 'long and loud'. This also alerted the children to dash into the village, this time to catch the fire engine as it turned into London Rd with its bell clanging.

The village, pre M6, was of a 'cosy size'. There was the original village centre with ribbon development along the main roads and, from about 1950 onwards, there were three areas of council housing:- Rees Crescent, Northway and Westway. Most of the young children in the village at that time attended the County Primary School on Macclesfield Rd, now the Catholic Church. Those living west of the A50 had to be shepherded across the centre of the village at the traffic lights by the 'lollipop lady'. For many years this service was provided morning and afternoon by Mrs Buckley. On their way to school the children could stop to buy sweets either at Mrs Warburton's, 'up the steps' next to the Co-op, or at Mrs Dale's on Macclesfield Rd. We weren't so careful of our teeth in those days. For those on the 'wrong side' of the village getting to Sunday School could be a challenge in the autumn. This was the season of 'Blackpool Lights' and the way across the road into church would be blocked by coaches heading for Blackpool queuing at the traffic lights.

The 1950s were the years of the 11 plus exam so, after being together through their primary years, the children would leave Holmes Chapel in many different directions on their way to senior school each morning - to Middlewich, to Sandbach for the Boys Grammar and to Crewe for the Girls’ Grammar School. After 1957, when a new grammar school opened in Congleton, most of the girls from Holmes Chapel went there. Some children had to cross London Rd to catch the school bus without the help of the 'lollipop lady'. The coach for Congleton picked up the girls on Station Rd so for girls living west of the A 50 this might mean negotiating first, Chester Road, which didn't have a footpath, and then the lorries on the A50 at the junction between Chester Rd and Station Rd. This was always a challenge even when the traffic was stationary right through the village which often happened. The M6 relieved some of these difficulties.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" February 2020

Click here to return to top of page.

The College of Agriculture & Horticulture

Holmes Chapel was the original home of the Cheshire College of Agriculture, situated at Saltersford Hall on the site of Saltersford Bungalow at Saltersford Corner. It comprised of a 100 acre of farm and gardens and was established in 1895 to fulfill the need for agricultural and horticulture education in Cheshire. There was accommodation for 60 residential students who mainly came from the county.

Whilst the emphasis was on scientific and technical subjects it also gave tuition in all aspects of practical farming. Research work was also undertaken, both in the laboratory and on the land. The Horticultural Division was the only establishment of its kind in the country at that time. Two year courses were held in the sciences of farming and culminated with the students sitting the exams of the Royal Agricultural Society. Later, in conjunction with Manchester University, B.Sc degrees in agriculture were awarded. Farmers and private individuals used the advisory service provided. The College would report on anything from milk for its acid content, seed germination, grasses for permanent pasture and analysis of manure and fertilisers etc. The original Principal was James Scott Gordon. Later Mr T.J Young held the position and continued to do so throughout the College’s existence at Holmes Chapel.

By 1914 the college was well established and highly respected both in the county and nationall with 56 students, their ages averaging 16 to 20 years. At the outbreak of World War I, eligible students enlisted in the services. Consequently a large reduction in students interfered with the running of the College, a difficulty which continued throughout the War.

In 1916 the War Office agreed with the Board of Agriculture that suitable disabled soldiers and sailors could attend the college for training in agriculture and horticulture. However, once this agreement finished, it was decided the College was to be closed by the end of March 1917 as it could no longer justify the funding with the shortage of students. A reprieve came with the formation of the Women’s Land Army in 1917 and training courses for them were carried out at the College from May to October of that year. In January 1918 the Home Office applied to the County Council for the College to be used as a temporary annexe to the Bradwall Training School for young offenders, which was granted. The Training School took over the lease in 1919 and was fully established at Saltersford until it, too, was closed in 1954. Although for a time it was intended to reopen the Agricultural College at Saltersford Hall after the War, this never happened. Instead, it transferred to Reaseheath near Nantwich where it is today. The Training School took over the lease in 1919 and was fully established at Saltersford until 1954 when it, too, closed.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" March 2020

Click here to return to top of page.

What's In a Loaf?

During the 1930s Dr. Lionel Picton, who had been

the Holmes Chapel GP since 1903 and who was the subject of an earlier

feature in this magazine, devised a recipe for a wholemeal loaf which

became known as Fertility Bread. Dr. Picton was an advocate of healthy

eating and good nourishment. He strongly believed that a woman’s good

health was essential for fertility and the nurturing of a healthy baby.

An intended aid towards this was a wholemeal loaf made from locally

grown and ground wheat, mixed with half its weight in raw wheatgerm.

During the 1930s Dr. Lionel Picton, who had been

the Holmes Chapel GP since 1903 and who was the subject of an earlier

feature in this magazine, devised a recipe for a wholemeal loaf which

became known as Fertility Bread. Dr. Picton was an advocate of healthy

eating and good nourishment. He strongly believed that a woman’s good

health was essential for fertility and the nurturing of a healthy baby.

An intended aid towards this was a wholemeal loaf made from locally

grown and ground wheat, mixed with half its weight in raw wheatgerm.  Dr

Picton believed that Vitamin E, found in wheatgerm, was an essential

aid to fertility. Moreover, the ingredients had to be absolutely fresh

and baked within 48 hours as the potency of the Vitamin E would

diminish. The resulting loaf was both nutritious and tasty. A patent

was obtained by William Mandeville and production began at his bakery

on Macclesfield Road, Holmes Chapel.

Dr

Picton believed that Vitamin E, found in wheatgerm, was an essential

aid to fertility. Moreover, the ingredients had to be absolutely fresh

and baked within 48 hours as the potency of the Vitamin E would

diminish. The resulting loaf was both nutritious and tasty. A patent

was obtained by William Mandeville and production began at his bakery

on Macclesfield Road, Holmes Chapel.  The

wheat germ came fresh off the rollers of a Liverpool mill and the fame

of the loaf soon spread. Loaves were sent far and wide by post and the

bakery received letters asking for advice from all over the world!

However, its popularity was short lived. Production ceased with the

commencement of the Second World War as the Ministry of Food cut short

supplies of the wheatgerm as a war measure and post war production

proved impracticable. Unfortunately there are no figures available as

to an increase in the population attributable to the bread.

The

wheat germ came fresh off the rollers of a Liverpool mill and the fame

of the loaf soon spread. Loaves were sent far and wide by post and the

bakery received letters asking for advice from all over the world!

However, its popularity was short lived. Production ceased with the

commencement of the Second World War as the Ministry of Food cut short

supplies of the wheatgerm as a war measure and post war production

proved impracticable. Unfortunately there are no figures available as

to an increase in the population attributable to the bread.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" April 2020

Click here to return to top of page.

Holmes Chapel on VE Day 1945

The Second World War had been going on for six years since 1939 and the world had changed even for people in the relatively remote village of Holmes Chapel. Many men and women had joined the services and left the area. However, unlike the First World War the community at home was very much involved in the war machine.

The wallpaper factory was now producing munitions which were stored at a Royal Army Ordnance Corps depot along Manor Lane. There was an airfield at Cranage from which flying missions attacking enemy aircraft took place. In Byley there was a factory where Wellington Bombers were built. Troops had been billeted in the village; evacuees were living with families; American servicemen had stayed at The Hermitage and Sandiford Cottage; Italian and German POWs had stayed at the Bull and Sandiford Cottage; and people were subject to rationing, growing their own food. Even grass verges were ploughed up to "Dig for Victory".

And then on May 7th 1945 reports came through on the wireless that the war in Europe was over and VE Day was declared for Tuesday May 8th. Not many people are now alive who can remember that day in Holmes Chapel but we have learnt that it was a day of spontaneous celebration centred on the Good Companions Hotel which was on the site of Lovell Court in the centre of the village. This was a brand new hotel only opened just before the war and had a large car park at the front. This became the location for drinking and dancing well into the night. A band played on a flat bed trailer which had been brought along.

There are reports of flags displayed around the village but sadly no photographs have been found to confirm this. No doubt it was more important to celebrate than take photographs.

Following a day of celebration, apart from thanksgiving services and peals of bells, it appears life went back to normal and people gradually adjusted to peace time although rationing continued and in fact became more severe in the years to come. This may have influenced the Parish Council who decided not to support the Victory Celebrations planned for June 1946 proposed by the government. Clearly for the village of Holmes Chapel one day of celebration was enough.

We would love to have included a photo of Holmes Chapel celebrating and maybe you have one in your album you could let us see. This photo at least illustrates the general mood on the day.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" May 2020

Click here to return to top of page.

Cranage Airfield

The recent commemoration of the 75th anniversary of VE day revived memories locally of the wartime airfield at Cranage. Many readers will want to know more about RAF Cranage and its role in the defence of the nation.

The site of Cranage Airfield was chosen for use as a training and maintenance unit in August 1939. Originally just a grass airfield with three runways, these were upgraded with Army Track Wire Mesh then replaced with American Metal Planking in April 1943. It had 8 blister hangars for maintenance use. At Byley, close to the airfield, was a Vickers Armstrong factory assembling Wellington bombers. The completed aircraft would be towed from the factory to the airfield for their first test flight and then onward for delivery.

Several flying units were based at the airfield. The first was No 2 School of Navigation formed on October 21st 1940. It operated twin engine Avro Ansons for training navigators. In 1942 it was renamed the Central Navigation School and was increased to 58 Ansons. From December 1940 the airfield also housed its first operational squadron. 96 Squadron was equipped with Hawker Hurricanes and operated in the night air defence role. It mainly protected the industrial and port areas of Liverpool. Then, in July 1941, 1531 Flight was formed as a Beam Approach Training Flight using the Airspeed Oxford. When the Central Navigation School was moved out to RAF Shawbury, Cranage became the home of the Repair and Inspection Squadron of Servicing Wing.

In 1944 the USA Army Air

Force 14th Liaison squadron worked from the site operating Sentinels.

This unit was part of the 9th Air Force and General George Patton’s 3rd

Army. Patton himself visited Cranage Airfield in May 1944 from his

nearby headquarters at Peover Hall where he was staying while he

prepared for Operation Overlord and the Normandy landings. As the war

drew to a close flying at Cranage was reduced. A detachment of No 12

Pilot Advanced Flying Unit operated there from February 1945. The only

flying unit operating from the airfield after the war was No 190

Gliding School which was formed in May 1945 using Kirby Cadet gliders.

It operated from the site for two years.

In 1944 the USA Army Air

Force 14th Liaison squadron worked from the site operating Sentinels.

This unit was part of the 9th Air Force and General George Patton’s 3rd

Army. Patton himself visited Cranage Airfield in May 1944 from his

nearby headquarters at Peover Hall where he was staying while he

prepared for Operation Overlord and the Normandy landings. As the war

drew to a close flying at Cranage was reduced. A detachment of No 12

Pilot Advanced Flying Unit operated there from February 1945. The only

flying unit operating from the airfield after the war was No 190

Gliding School which was formed in May 1945 using Kirby Cadet gliders.

It operated from the site for two years.

Cranage Airfield did suffer casualties, aircraft crashed on take off and landing and during test flights after aircraft had been assembled or repaired. The war graves of 16 aircrew can be found in the churchyard of St John, Byley. These include 13 from the UK, 2 Australians, 2 Canadians and 1 from New Zealand. Their ages range from 19 to 31, they made the ultimate sacrifice in defence of this nation.

Flying ceased from the site in 1947 but was used for storage

and maintenance. In 1954 the airfield was allocated to the USAF as a

satellite for their site at RAF Burtonwood. It was home to a detachment

of 7493 Special Investigation Wing and 7523 Support Squadron and a

number of their non flying units were also stationed there. At the end

of June 1957 the USAF returned the base to the RAF and it was closed

permanently in 1958 with the hangars being dismantled and sold. Remains

of part of the airfield defences of RAF Cranage survive well, including

some of the battle headquarters, a gun pit, three  pillboxes and a night accommodation aircrew sleeping shelter. These are

rare survivals nationally and they illustrate well some of the measures

taken to protect airfields from the threat of capture. These airfield

defences were constructed in two phases. In the 1930s they were

designed to provide protection from air attacks but in the spring of

1940 it was realised that airfields could be targets in a strategy

aimed at capturing them and so pillboxes and battle headquarters were

added. Historic England listed the airfield remains as a Scheduled

Monument in July 24th 2002.

pillboxes and a night accommodation aircrew sleeping shelter. These are

rare survivals nationally and they illustrate well some of the measures

taken to protect airfields from the threat of capture. These airfield

defences were constructed in two phases. In the 1930s they were

designed to provide protection from air attacks but in the spring of

1940 it was realised that airfields could be targets in a strategy

aimed at capturing them and so pillboxes and battle headquarters were

added. Historic England listed the airfield remains as a Scheduled

Monument in July 24th 2002.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" June 2020

Click here to return to top of page.Holmes Chapel's Water Supply

In the 19th century the village had no mains water. People had to rely on private groundwater wells, rainwater collected and stored in tanks (as at The Hollies) and natural springs. There were at least three of these :- one half way down the bank out of the village on Knutsford Rd known as The Spout, Nicker’s (or Nicho’s) well half way down the bank leading to The Hermitage (closed in 1934) and a well on London Road near Victoria Avenue (closed in 1916). In 1909 a scheme was put forward to supply piped water to Holmes Chapel. Mr Wyatt the engineer estimated the cost to be £1,950. Fourteen tenders were received and a tender for £772 from Stanton Iron Co was accepted. This tender was perhaps for the supply of pipes only because by 1910 Holmes Chapel was borrowing £1631 for the laying of water mains to the village. The water was brought from Delamere through Middlewich, with a booster pump at Sproston. This supply proved to be inadequate and properties beyond the village boundary such as Cranage Hall could not be supplied.

By 1915 complaints were being made via the clerk of Congleton Council to be passed on to Middlewich Urban District Council. The water pressure at Middlewich was 50lbs but Holmes Chapel was only receiving 8-10 lbs such that sometimes the farmers could not get ‘enough water to cool the milk’. There is a height difference of thirty metres between Holmes Chapel and Middlewich and the problem was thought to be one of pumping and not rainfall. The shortage was eventually solved by turning off a valve to restrict the supply to Middlewich. In May 1916 the water was turned off for a whole day without warning and the people of Holmes Chapel complained that they had had to ‘go back to the old times and take their cans and buckets to the pump’. Mr S Moss was put in charge of the mains in 1917 and was responsible for flushing the system once a month. In 1926 he reported that water was being wasted and a leaflet was sent to all householders urging them to limit their consumption, which was much lower than we would regard as acceptable today. By the 1930s attempts were being made to improve the supply throughout mid Cheshire but progress was slow. Only in 1945 were local newspapers able to report that the Northwich and Congleton water project was complete. The new seven inch water main now ran from the reservoir at Heyeswood near Hartford to the boundary of Congleton passing through Allostock, Byley, Holmes Chapel and Goostrey. Dignitaries made a tour of the trunk and finished at the Good Companions in Holmes Chapel where they were hosted by the contractor. The route via Allostock and Byley would explain the origin of the name ‘Pump House Farm’ in Byley. Water to the village now comes from Lake Vyrnwy in mid Wales and there is a covered reservoir at the high point of Broad Lane just outside the village.

| |

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" July 2020

Click here to return to top of page.Spanish Flu in Holmes Chapel 1918-19

Just over 100 years ago, Holmes Chapel villagers were fighting a pandemic very similar to the one we are suffering today. Dr Picton was the only doctor in the village and he was assisted by a local nurse paid for by charitable contributions. All patients had to pay for doctor’s visits and medicines.

Here is a timeline of how the crisis unfolded in the village:

Spanish flu arrived in the village on Thursday 10th October 1918. Cranage School’s Headteacher reported “Influenza epidemic began suddenly. 10 cases reported today. On Tuesday 15th, the Crewe Chronicle reported that “Influenza has broken out in Holmes Chapel. At the Paper Mills on Macclesfield Road, 13 persons who became affected were compelled to cease work.”

On Wednesday 16th, the Head of the Mixed School on Macclesfield Road reported “Attendance this morning is very bad, as Spanish Influenza has broken out. Ten children who are absent have the complaint, while others at school show symptoms.”

On Thursday 17th, Cranage School Head reported “33 cases of influenza. School closed until 4th November.” The Mixed School reported “Attendance only 58% of roll [125]. The Medical Officer has closed the school until 18th November due to influenza.”

On Friday 25th, the papers reported “The epidemic has spread alarmingly this week, and there is hardly a family which has escaped. Over 30 cases among the boys at [Saltersford] College are reported.” A local dance was cancelled that weekend.

On Monday 18th November, the Mixed School reopened, although the Headmaster was reported as “suffering from pleural pneumonia” and only returned on 16th December.

The epidemic was still on-going because a Jumble Sale on 23rd November was postponed for a fortnight “in consequence of the severe epidemic of influenza which has been raging in the Parish for the past few weeks”. The epidemic then went away over Christmas, but in the New Year returned to the Mixed School.

On Friday 17th January 1919, Attendance worsened steadily this week. Today 40 children are absent suffering from colds and croup.” On Monday 20th the Head reported, “Today 60 children present out of 125. There is every symptom of a whooping cough epidemic or some chronic throat and bronchial trouble.” On Friday 24th, because of a steady decline in numbers, the school was closed for a fortnight.

After the epidemic had subsided, the Medical Officer reported that there had been seven deaths in Holmes Chapel due to influenza. From the papers we know the names of four: Walter Denby (53), William Postles (32), George Pierpoint (41) and George Cartwright (52).

From the middle of February 1919 (Week 18), Holmes Chapel appears to have been finally clear of the epidemic.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" September 2020

Click here to return to top of page.What Llyod George Wanted to Know (about your house)

If your house was built before about 1910 you can get an interesting snapshot of what the house was like at that time. This is thanks to a Budget presented by Lloyd George in 1909 which proposed taxing land which could have value beyond that of agricultural land. In order to identify this, a survey was carried out to value land all round the country. It produced detailed maps, including one of Holmes Chapel, on which the owner of every piece of land was identified. It also described any property on that land and who was living there at the time. So, for example we know that the occupier of the Police Station on Middlewich Road was Sgt Samson Bowyer. ‘The house was in good condition and had an office, a large living room, 2 cells each fitted with wooden beds and WC and a yard for exercising. Outside was a coalhouse a WC and a kennel.’

The records tell us whether the house had a water supply or used a well, what condition the house was in and how the waste water was disposed of. Very few houses had a water supply directly into the house and most drainage was into the nearest stream. Hot running water was very new and only the local plumber seemed to have this luxury. Electricity for most people was a dream and only two houses in the village, Sandiford and The Hollies had their own generator and batteries. The farms and small holdings were described in detail even saying how many cows they could accommodate and what was grown in the fields. For example there was tying for two cows at Saddlers Close, the home of Dr Picton.

All this information can be linked to the census which took place in 1911 so that for every house it is possible, with a little detective work, to not only have a description of the property but find out who was living there and how they earned their living. For any local historian or owner of an old house this is a treasure trove of information.

For those who want to find out more about an old property in Holmes Chapel, much of this information has been coordinated into a booklet called ‘Holmes Chapel around 1910’ which can be purchased from the Print Room in Church Walk.

Here is an example of what can be learnt:

In 1910 this cottage on Macclesfield Road was already old. There was a small garden area and paved yard with a pumped water supply. Accommodation comprised a living room, back kitchen and small wash scullery and 2 bedrooms. There was a coal shed and earth closet outside. The rent was £8pa. Over the door was a date of 1746 and the letters TBH indicating the house had been built or renovated by Thomas Bayley Hall who lived at the Hermitage and owned many properties in the area. Thomas Venables (66) lived here with his wife Sarah aged 62. He worked as a farm labourer.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" October 2020

Click here to return to top of page.Thomas Royle Kay - WW1 Soldier

This is the story of Thomas Royle Kay of Holmes Chapel - a WW1 soldier –a Private in the King’s Regiment – a forgotten hero. He volunteered at the start of the war in 1914, and his Battalion moved to France, near Nieppe south-west of Armentieres on 25th September 1915. On 30th April 1916 he was part of the British forces subjected to a gas attack at Wulverghen. Some but not all of the defending troops had rudimentary gas protection helmets, however the attack caused 562 casualties of which 89 were fatal. In the summer of 1916, his Battalion moved south to the Somme valley. The Battle of the Somme took place between 1st July and 13th November where 419,654 British & Commonwealth casualties occurred with 95,675 killed or missing. Just on the first day, there were 57,470 British & Commonwealth casualties, with 19,240 men killed or missing.

On 14th July, at the Battle of Bazentin Ridge, his Battalion attacked the German defensive position at 3:25 am after a five minute bombardment. Field artillery fired a creeping barrage and the attacking waves pushed up close behind into no-man’s land, leaving them only a short distance to cross to the German front trench. The attack was successful, but was not followed up due to communications failures, casualties and disorganisation. The numbers of casualties are recorded as 9,194 with about 3,000 killed or missing. Thomas Royle Kay was one of the missing that day. He has no known grave.

Thomas’ mother Annie lived in Holmes Chapel with her mother and father. In the early 1880s, Annie’s father (Thomas Kay) emigratedto Australia and became a farmer. Then in October 1886, Annie and her mother were staying in the Australian Immigration home in London awaiting passage to Australia to join with her father, when she gave birth to Thomas Royle Kay. Records show that Annie’s mother continued to Australia two days after Thomas’ birth, while Annie returned to Holmes Chapel, where she later had Thomas christened in St Luke’s. In 1888 when Thomas was two, Annie abandoned him and left to go to Australia to be with her parents. Thomas spent his early life living in Holmes Chapel, but by 1901 (aged 15) he was living at Wheelock Wharf, where he learned the trade of a canal boatman. He met Elizabeth Hodson who belonged to an established Cheshire canal family with whom he had a son in 1908, Thomas Hodson Kay.

His name is inscribed on the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval, overlooking the Somme battlefield, but nowhere else. Given that he grew up in Holmes Chapel, shouldn’t he be named on our Cenotaph, and remembered on our Roll Call every Remembrance Sunday?

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" November 2020

Click here to return to top of page.The Spy, the Red Lion & a Piece of Glass

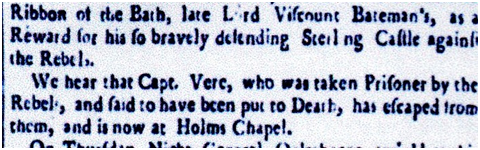

Who would have expected that Holmes Chapel might have been the venue mentioned in a spy story from the days of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the 1745 Jacobite revolt? This may well be true.

|

|

Captain John Vere (sometimes called Weir) was a British intelligence officer. According to one commentator, he was the most notorious spy of his time. Our story starts on 2 December 1745 when an advance party of Scots, went forward at night towards Newcastle-under-Lyme. When they reached the Red Lion at Talke (long since disappeared) they found a group of British soldiers including John Vere. Most of them escaped through windows but the Scots seized Vere, who they knew to be a noted spy. The initial thought was to execute him at once but instead he was tied behind a horse and taken barefoot to Congleton. There he was interrogated by Prince Charles and Lord George Murray. In order to save his life, he exaggerated the size and position of the army sent to quell the rebellion under the Duke of Cumberland. He told them that the British troops were in such numbers that the Jacobites stood no chance of survival. Lord George bluntly told the Prince that he and his army should return to Scotland, which they did shortly afterwards.

Now the story is not too clear, but there is a newspaper article in the Stamford Mercury of February 1746 which states that Vere escaped and had been seen at Holmes Chapel.

Though seen in Holmes Chapel, it was maybe still as a prisoner not escapee, as other reports say that he was taken to Carlisle by the Scots and subsequently released by the English after the fall of Carlisle Castle.

Did Vere and his captors stop a while at the Red Lion in Holmes Chapel, at that time an important coaching inn? If they did, it might explain the pane of glass on a window on the first floor which has inscribed on it “and preserve Prince Charles Amen I prey God”, perhaps left by his captors. After his release, Vere subsequently gave evidence in the treason trials that followed against Jacobite prisoners. One Scottish commentator wrote “This Vere….. was conducted back with us to Carlisle - how unfortunate for us, that he was not put to death, considering what he has since done!-but his life was saved through the innate clemency of the Prince, though he merited the worst punishments.”

No one knows for sure how that pane of glass ended up in a window at the Red Lion, but this is one possibility.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" December 2020

Click here to return to top of page.Road Developments in Holmes Chapel

Holmes Chapel grew, probably from the 13th century, at the junction of two routes. The main route was the north-south road known from early medieval times as the Great Route to the North, providing a link between London and Carlisle and pre-dating the Great North Road on the east side of England.

For centuries, road travel was by walking or horse. The horse was usually ridden, but eventually waggons drawn by teams of up to eight horses would haul large loads and later the trap and carriage appeared, having been developed in Europe. These though, were the preserve of the rich; most people still walked, with journeys of up to seven miles being commonplace.

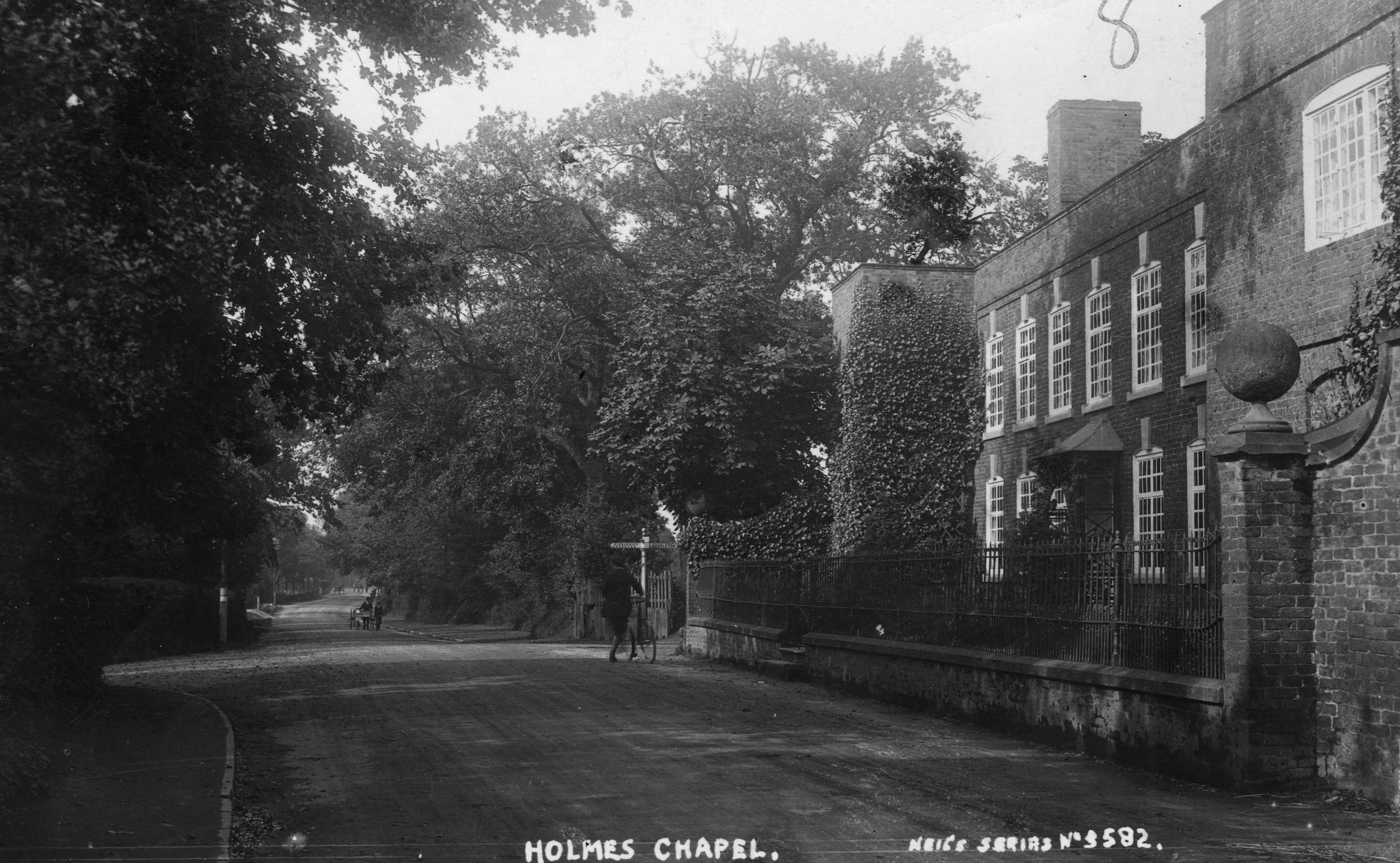

The Square Looking North

The roads themselves were poorly maintained, just tracks with no durable surface; dry, hard and dusty in summer and either a mud-bath or covered in snow and ice in winter. A journey from Glasgow to London in 1758 took 12 days on horseback. What little road maintenance carried out was provided under law by the parishes, with four days unpaid labour required of each parishioner. Inevitably, such work as was done focused on the parish itself. Roads between parishes were still poorly maintained. Thomas Steel is recorded as being appointed Surveyor to the township of Church Hulme in 1727 with responsibilities to provide cart-ways and horse causeys to market towns.

With increasing trade and commerce, the inadequate state of the roads became a serious issue and laws were passed by Parliament permitting local Justices to charge tolls which were used to improve the roads. This proved insufficient so further legislation was enacted to allow the formation of Trusts which had the rights over a length of road and could erect gates surmounted with pikes and toll houses to enforce payment for passage. They could also borrow money to improve the roads, paid for by the toll charges. These were the turnpike trusts. There were three turnpikes through Holmes Chapel - Lawton to Cranage (now the A50) opened in 1731; Nantwich to Congleton via Middlewich (now the A54) opened in 1753 and Holmes Chapel to Chelford (now the A535) opened in 1797.

The last one is of the most interest locally as the toll house still remains, now incorporated into a house, just east of Saltersford Bridge and well worth taking a look at. The Lawton-Cranage turnpike had a toll gate at or near Iron Bridge Farm, according to a map of 1842. Further north there was another toll gate at Cranage on the site of what is now the tyre depot. Other notable features along many turnpikes were smithies. On the Lawton-Cranage turnpike they could be found at Cranage, Holmes Chapel, Brereton, Arclid, Smallwood and Rode Heath. No doubt all the horse drawn traffic provided plenty of business!

Turnpikes were not universally welcomed. Manufacturers and traders benefitted from easier and faster movement of goods, but costs were increased by the toll charges. It is recorded that Edward Hall (Snr) of Cranage Forge complained that the toll costs were too high, given the number of waggons bringing limestone and coal in, and shipping finished goods out. The Turnpike era lasted until the 1880s when responsibility for road maintenance was given to the new County and Borough Councils, but they had been in decline since the coming of the railways from the 1840s.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" February 2021

Click here to return to top of page.Holmes Chapel Stagecoach Services

The first stagecoach services in England began in the early 1600s, but were restricted to summer only travel due to the abysmal state of the roads. Fifty years later routes from London were serving several Northern towns including Preston. It is possible, but not certain, that the Preston service passed through Holmes Chapel, given its location on the historic Great Route to the North. Journey times were in days as only one team of horses was used, but by 1734 the system of “staging” horses, i.e. exchanging them approximately every 10 miles became common practice. This lifted average speeds from 5-6 mph to 9-10mph – a halving of travel times.

The earliest record of the Red Lion Inn in Holmes Chapel is from 1625. It would have been well placed to provide accommodation and hostelry for passing coaches, a demand which would both grow and sustain it over the next 200 years. There must have been steady progress in stagecoach services locally, as Dick Turpin, the infamous highwayman of the 1730s, was recorded as frequenting Ye Olde Black Bear in Sandbach. He wouldn’t have been there just for the ale!

By 1760 the “Flying Machine” coaches were calling twice a week at the Red Lion, en-route between London and Warrington / Manchester. The one-way fare was £2 2s (£2.10) inside, with half fare for an outside seat. You must have had fortitude for that!

Another significant part of the development of road transport was the mail coach. The Post Office had used post boys on horseback for many years and was resistant to the use of stagecoach services. Following a protracted campaign mail coach services commenced and grew rapidly. By the time of their demise, mail coaches were running some 136 routes, using 700 coaches. The London-Manchester service ran via Congleton, missing out Holmes Chapel, but the Royal Mail from Liverpool to Birmingham did call at the Red Lion.

Services had expanded rapidly through a combination of improved coach design, better roads and horse staging, delivering faster, more reliable services. Some idea of local services can be seen in the following table of coaches calling at, or passing through the village in 1830 and running to a fixed timetable, which was quite a feat for its time.

| SERVICE | ROUTE | RED LION | GEORGE & DRAGON | BEAR'S HEAD BRERETON |

| THE AURORA | Liverpool -Birmingham Daily |

21:15 (S) 15:45 (N) |

||

| THE BANG-UP | Liverpool-Birmingham Daily |

13:00 (S) 14:00 (N) |

||

| THE ROYAL EXPRESS | Liverpool-London Daily |

20:30 (S) 15:00 (N) |

||

| THE ROYAL MAIL | Liverpool-Birmingham Daily |

24:00 (S) 03:00 (N) |

||

| THE UMPIRE | Liverpool-London Daily |

19:00 (S) 11:30 (N) |

Stagecoach services became a huge business, which at its peak required over 150,000 horses and employed very many people. Sadly, the advent of railways spelt their demise. Nationally, some services lasted until the 1880s, but the golden era was long gone. Technological progress had killed them off and no longer would a coach and four clatter through the village.

This article was published in "The Villages Mag" March 2021

Click here to return to top of page.Sandiford Cottage

On the site of the Holmes Chapel Fire Station once stood a large house in extensive grounds, which were bisected by the Sandyford Brook. This was Sandiford Cottage, built in the late nineteenth century as a private home, but which had many uses before it was demolished to make way for the fire station and the shopping precinct. Some of the outbuildings, converted into a smaller house, still stand at the rear of the present day barber’s shop, once the village post office. In the 1880s Sandiford Cottage was the home of the Misses Royd; by 1891 it was occupied by Sydney Roberts, a chemical manufacturer, and his family and servants. In 1897 the Holmes Chapel and District Horticultural Society was allowed the use of the grounds for the annual flower show, with a show tent, band and amusements and the tea tent in the adjoining field, a privilege which was to continue when Frank A Haworth became the tenant. The Land Tax Survey of 1910 records that the house had six bedrooms, two nurseries, two bathrooms and a servants’ hall, with four bedrooms for staff, making it a very substantial residence, lit by electricity when most homes relied on oil or gas lamps. Outside there was a coach house, stables and loose boxes, a garage, engine and cell house and even a schoolroom. Mr Haworth had, that year, bought the house for £2,300.

Frank A Haworth was a pillar of the local community, serving on many committees, including the fund for Belgian refugees who came to Holmes Chapel during the First World War. He was active in recruiting local men for Kitchener’s army and the Volunteer Training Corps for home defence, serving in the latter himself and hosting band concerts in the garden of his home. However, once the war was over he seems to have moved out of the property, and it was rented by the Church of England until a newly built vicarage on London Road was ready in 1930.